-

-

-

-

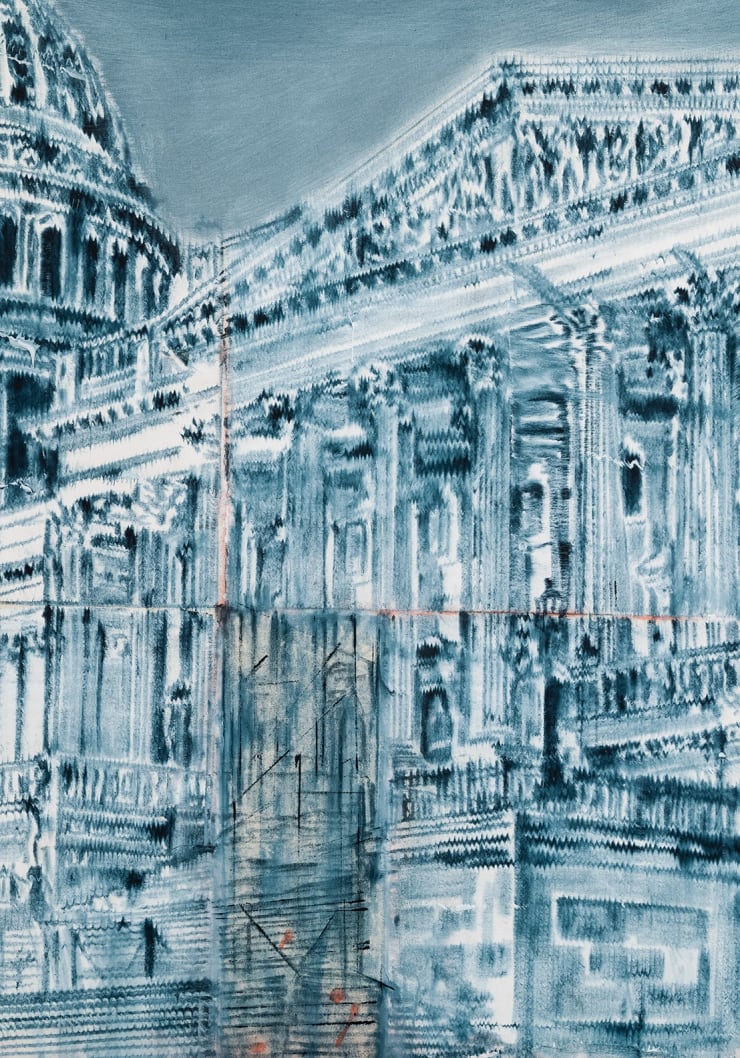

This is not the first time Tacla has painted the Capitol. Below are two paintings that show federal government buildings, including the Capitol and the Pentagon.

Both of these institutions play important roles in our lives--one drafts laws and confirms Presidential nominations, and the other oversees the U.S.'s military affairs. Notably, these two paintings also turned out to be somewhat prophetic, as major conflict later visited both sites.

-

Photograph of the artist's studio showing The Distribution of the Primes, c. 1990s

Photograph of the artist's studio showing The Distribution of the Primes, c. 1990s -

Some of Tacla's other paintings of symbolic architecture represent the moment after the devastation has occurred. Below, paintings E, H and I present scenes from the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 in the U.S. Live Organisms from 1996 memorializes a scenes from the domestic terrorist bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma in 1995.

-

In 2007, critic Richard Vine wrote about Tacla's depictions of bombed and leveled architecture in an essay fittingly titled Art Among the Ruins. The essay is included here in its full length to further contextualize the artist's treatment of architecture.

-

Art Among the Ruins

By Richard VineTacla seeks to unite the private, suffering, persevering self and the battered body politic in a timeless fashion, without ever violating the historical specificity of his visual sources.

The modernist imagination is littered with rubble, from the massive devastation of two world wars to Freud's metaphor for the interior self as a jumbled, multi-layered archeological site--a city built upon strata of its own former habitations. Indeed, the very project of modernism--the continuous "make it new" of Ezra Pound's 1934 dictum--implies not only a progressive building-up and creating afresh but also its complement, a relentless tearing down, dismantling, and clearing away of whatever is past, depleted, or simply in the way. Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, and all the rest, yes--but not without first decimating the Academy, the Salon, the tenets of good taste, and the centuries-old patronage system. In our era this is, largely, what it means to be a "developing" nation or an adaptive, innovative individual.

In his new body of work, Jorge Tacla has given visual form to this persistent dilemma. The nine large-scale paintings fall into two groups: Trauma #1 and #2 offer close-up fabric- and flesh-related images, while the seven canvases of the Escombros series (the Spanish title translates as "Rubble" or "Debris") depict a bombed-out cityscape based on a newspaper photo from Beirut. Tacla blends these seemingly disparate references into a single cohesive, though multivalent, viewing experience--a meditation on wounding, rife with latent analogies between human skin, the social fabric, and our built (and often willfully demolished) environment.

Looking closely at Trauma #1 (2006), the earliest work in the grouping (all others are from 2007), we see that the artist clearly began with a fascination with both actual and figurative interweaving. Thread-like and organ-like forms are knit together in a loose, flesh-hued network. If the vulnerability of exposed intestines is evoked, so too are the exceptional flexibility and strength of such systemic interconnections, whether physical or social. Trauma #2 takes us even closer, its myriad globular components resembling pinkish skin cells, disrupted by an ominously redder central bruise or incipient cancer.

With the Escombros series the focus shifts, in effect, to the civic body. In each example, we see--from various ranges of view--shattered and half-fallen buildings rendered in lacey marks that retain associations with cloth or porous hide. It is not that we are seeing ruin through a veil, but that the devastation itself is endowed with openwork texture, at once visually penetrable and liable to collapse. There are passages (in Escombros #1 and #5) that recall Victor Hugo's haunting, architectural dream-sketches; elsewhere (in #3, #6, and #7, for example), the fracturing of space within damaged structures becomes almost Cubist.

Despite restricting himself to a fixed subject and head-on point of view--choices that force the viewer to confront war's difficult facts and limited options--Tacla achieves varied effects through his deft manipulation of composition, color, and surface. No dead or wounded bodies are to be seen; buildings are the human stand-ins here. Yet we are plunged deep into the site of conflict by virtue of horizon lines that are either exceptionally high (in #2, #5, and #6) or nonexistent (in #3, #4, and #7). We are within the rubble, and there is, visually, no escape. Where a strip of sky appears, it is streaked and mottled, reflecting psychological turmoil like the troubled heavens in a Munich landscape.

Overall, the hues are muted and uniform, congealed into one or two chromatic blocks that give each painting, at a distance, the blunt impact of a big-field abstraction. By eschewing bright, "explosive" color, Tacla directs our attention not to a melodramatic burst of violence but to its lingering, soul-numbing aftermath. His oils and acrylics are diluted with heavy admixtures of turpentine and water, and overlaid with a dark hand-drawn tracery that, upon close inspection, suggests broken walls, exposed interiors, aimless staircases, and blown-out windows.

The paintings' surfaces are matte, as though intended to transmit a subdued mourning. In fact, marble powder has been worked into the pigments, so that--in a heightening of the aftermath effect--everything appears as if covered by a thin layer of settling dust. Although what we see must have been preceded by a horrific blast, the formal emphasis of the work is on an informed but dispassionate response--equipoise in the face of tumult, forbearance amid murderous passions.

Thus one can see in Tacla's Escombros a certain affinity with the shards and fragments, echoes and half-remembrances of T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land. Both works contemplate loss and confusion, both convey a wounded sensibility, both seek to redeem disaster through artful equanimity. Often, very personal crises lie behind such therapeutic works. But biographical impetuses, though vital to the origin of a work of reclamation, are largely irrelevant to its critical worth. We value The Waste Land for, among many other things, its melding of countless voices and emotional registers and levels of diction. We stand in awe of Eliot's ability to persuasively connect wide-ranging allusions (to ancient Greece, the Bible, WWI, Dante, vaudeville, cheap pubs, pagan myths, etc., etc.) and to bring them all into the poetic present, the eternal.

In Tacla's case, the components are less diverse but the resolution equally intense--think of Guernica not as Picasso commemorated it, at the frantic hour of bombardment, but the day afterwards, when each surviving citizen surveys the mute debris and asks how--and why--to begin again. It is a moment we all can relate to, even if we have never experienced literal war. Tacla seeks to unite the private, suffering, persevering self and the battered body politic in a timeless fashion, without ever violating the historical specificity of his visual sources.

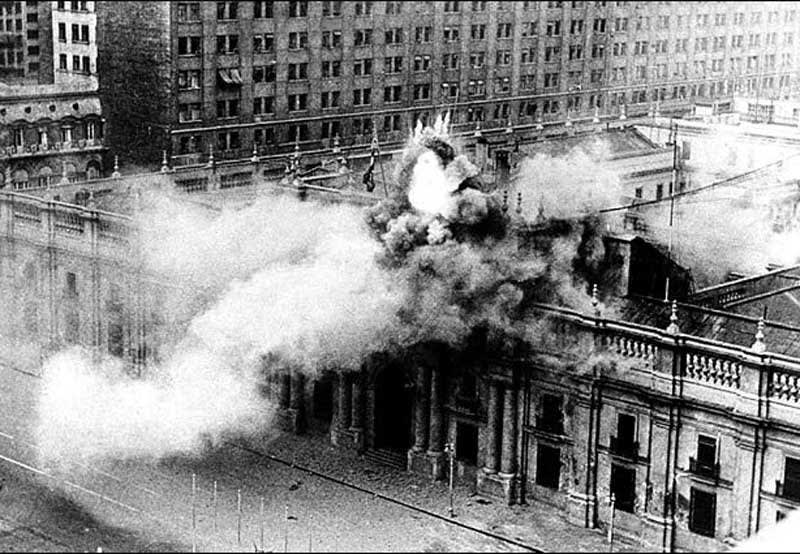

These mildly schematized, nearly monochromatic depictions of war-torn Beirut hark back to the artist's early treatments of La Moneda, the government building bombed in Santiago during the 1973 CIA-backed coup that overthrew Chile's leftist president Salvador Allende. At the same time, they also resonate with dreadful familiarity for anyone who, like Tacla, was present in New York on September 11, 2001, when the Twin Towers collapsed under assault from Muslim terrorists. Thus the political implications of these images are as tangled as their obsessive fretwork of lines, yet their basic human import is as simple, as foursquare as their underlying Rothkoesque compositions. In an age of globalized conflict, as W.H. Auden once wrote, "We must love one another or die."

Hope, however, does not exactly spring eternal in Tacla's pictorial universe. In fact, desiccation and waste are among his longstanding themes, rehearsed in paintings (such as Land Claim of 1995) haunted by his memories of the Atacama Desert. Such scenes of desolation put the emphasis in Auden's sentiment where it truly belongs--on the must. Even the most successful life, these new works remind us, is riddled with projects begun and abandoned, relationships built and destroyed, plans marvelously executed and plans scotched by cruel whim or changing circumstance. Our history, personal and collective, is built, as a great cathedral rises, in the midst of its own debris. In the long run--through age, accident, or disease--every biography ends in ruins. Yet Tacla's Escombros are not emblems of total despair. For their conceptual intelligence and technical finesse remind us that meaning--and perhaps even a disabused joy--can subsist in the artistry, the wisdom, and the compassion with which we confront our catastrophes.

-

-

La Moneda in flames, September 11, 1973.

La Moneda in flames, September 11, 1973. -

At the same time as Tacla was painting scenes of rubble and disaster, he was also drawing inspiration from buildings that embodied the promise of utopian ideals through modernist design. One of his chief subjects was the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Hugely influential, Wright's buildings helped define architectural style in the 20th century, serving as a paragon for future generations of designers. Wright aimed to create architecture that existed in harmony with the environment and with humanity; his buildings--both residential and commercial--underpinned the idea that a well-designed space could enhance the owner's life--as well as their society. Below are two of Tacla's Frank Lloyd Wright paintings, with one showing the infamous interior of the Johnson Wax Headquarters.

-

The artist in front of Nieuwe Kerk (the New Church) in Amsterdam

-

For more information about Jorge Tacla, please click here.

Architecture as Symbol

Past viewing_room